Interviewed by Visión RDN on April 29, 2023

There is no “Migrant Crisis,” There is an Imperialist Crisis

Originally interviewed by ANTICONQUISTA in March 2021

Revolutionary Struggle from the Bronx to Venezuela

Originally Interviewed by Moderate Rebels in December 2020

Relevant Documentaries to this Historical Moment as Humanity Confronts the Coronavirus

1. SRS, one of the Most Dangerous Viruses (PRE)

Solid scientific look at SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and its origins in 2003, with Hong Kong at the epicenter. Gives us perspective on what we are up against today. Coronavirus is almost like a SARS II in a sense that the U.S. ruling structures were not ready for. China was much more prepared.

2. The Truth About The Ebola Virus | Science Documentary 2019

In terms of understanding Ebola — beyond the racism and sensationalism of the mainstream and Vice hipster news — this is a unbiased, solid documentary.The opening scene of children in Liberia was touching. The Ebola River stretches 250 kilometers across the Congo by the way. How did the mainstream media mutate that word into something perceived as pure ugliness?https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=koGNve1i4Mw&list=LLQkgdty5_bmDrw19dolYZcg&index=2&t=8s

3. The Lockdown 1 Month in Wuhan

4. Vox’s Why New Diseases Keep Appearing in China

5. Vice: The Fight against Ebola

6. After Ebola: Nebraska & the next Pandemic

7. We Heard the Bells: The Influenza of 1918

8. Timeline: The Great Plague The Black Death

9. 93 Days

10. Contagion

11. Interview with Dr. W. Ian Lipkin who Breaks down Coronavirus

12. Outbreak

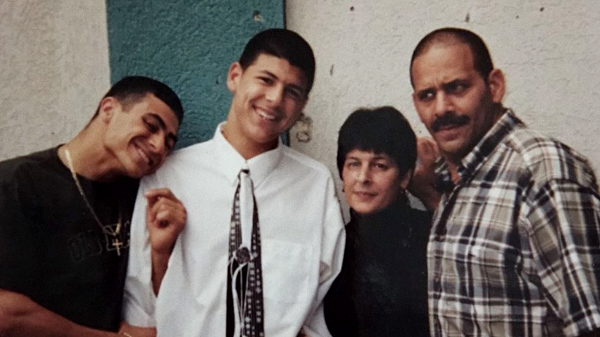

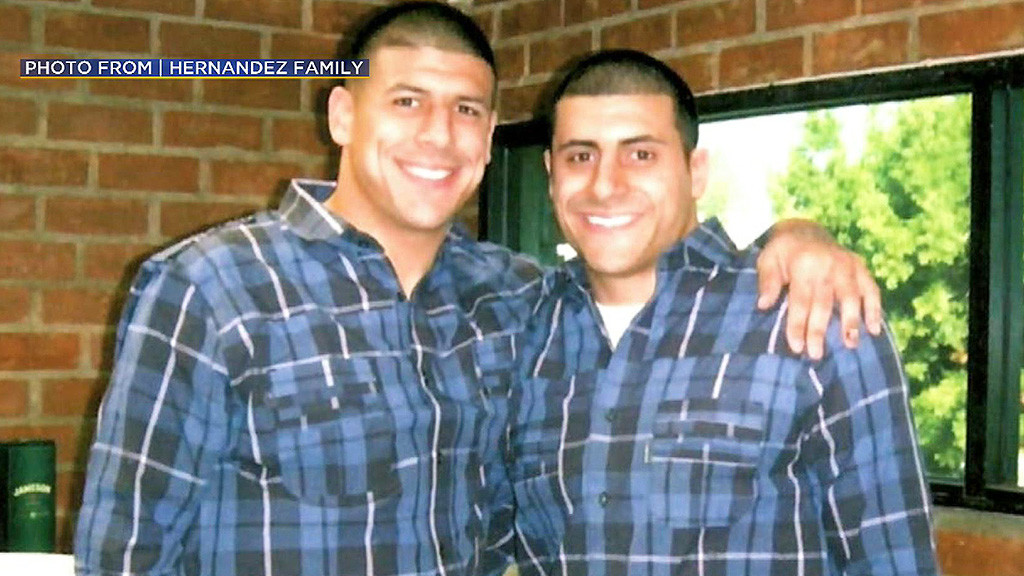

Trauma Silenced: Aaron Hernandez Beyond the Headlines

Hustling: All Day, Every Day…

When our son Dessalines was coming of age, we had to get him out of the South Bronx. A decade plus later, the South Bronx is still his home. Khalil Gibran reminds us parents:

“Your children are not your children.

They are sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you.

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.”

On a bitter frigid night on 149th st., Dessalines came back home Christmas after sixteen months away upstate. It was good to build with him & just walk through the hood saying what’s up to the old-school characters and hustlers on the corner who remembered us from the boxing and street days. Having my son, one of the human beings I most love and admire, back home, reminded me of so many survival and love-life lessons. I wrote this to my sons:

Hustling: All Day, Every Day

I love the hood. I gave everything for the hood. But the hood is a double-edged sword. It will take you under; it will elevate you. It will suffocate you; it will breathe life into you. It will drown you; it will eternalize you.

The block is schizophrenic and it makes you schizophrenic. It steels you as it dismantles you. It builds you up as it knocks you down. You’re so caught up, you can’t see there is something else out there. The perennial quest for survival produces a certain narcissism, dressed up with a fitted baby blue NY Yankees hat and tan timbs.

The backdrop is grim. A shoot-em up man in search of ghetto glory took out five people on 153rd and Courtland. There were NYPD helicopters in pursuit and dozens of police cruisers crisscrossing every block. This is what my son came home to? A war zone built to destroy us. A ghetto obstacle course. The warden and CO’s release you out the gates like:

Welcome home kid.

Here’s five bucks.

See what you can do now.

Don’t let anymore of that candy go up your nose.

Do the right thing kid!

This is home! An Black August night with Dead Prez bumpin’ in and out of double parked cars on the block. St. Mary’s Park hosts hundreds of families. The children run free. Hot food, cold beer and love are plentiful. The 90 degree air is electric.

Tempers flare and gunshots can break the peace at any given moment.

Block to block, you zigzag in and out of the horror. The herds of the homeless and fallen…the fentanyl, the street mechanics, the unwashed, the unseeable, the unheard, the paper bags, the shopping carts, the survivors…

Surviving, Always surviving but when do we get to live?

The mothers, the Sunday outings, the fathers, the cousins, the reunions, the laughs, the magic, the memories, the births and funerals.

Family is everything in the South Bronx.

Puerto Rican flags, Red Black and Greens, Dominican flags, Mexican flags, Honduran flags and American flags decorate bodegas where everyone knows your name.

The police brutality and neighborhood shootouts hover over our family affairs and holidays. Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and New Year’s Eve are times of merriment, cheer and church. The laughs, the memories and the nostalgias pile up from over the years. We unwind in the presence of our loved ones.

We Let Go

We Let God

We Let Good…

Mental illness?

What’s that?

We don’t have such luxuries.

There is no room to entertain weakness. You bully or you get bullied. We have seen dozens of grown men and women defecating themselves. Do you want to see us among the most alienated?

We lick our wounds, tighten our timbs and move on.

These streets and their overseers are the ill ones.

Who are we but

Spiritual burglars

Soul survivors

On 1 4 9, mental illness is nothing more than brokenness with twenty fancy white, petty bourgeois euphemisms. Pharmaceutical companies and rich people cash in on the very destruction they cultivated. A savage merry-go-round. Hop on board. Where else you going?

Forget about visiting another state or country homie, I am trying to get off this block…

In the words of Bertolt Brecht, “our very survival is a miracle.”

Understand: all this is designed to break us…black people, brown children, little girls, poor whites… the chicken spot, the liquor store, the churches, the broken glass, the talk shows, the laundromats, the leering glares and smirks from the police invaders…

What escape do we have?

The lure of hustling…the ghetto trap. To lay it all on the line like there is no tomorrow.

A hustler is the ultimate Buddhist; all he has is the present.

Tomorrow promises sirens, handcuffs and ten years long gone, Upstate, locked up in a box. You think I’m a be worried about what girl I’m talking to? Or whose wife she might be? Got more pressing concerns homie. The urgency is me.

There is a fire deep within me Unsettled Unsettling the weight of the historical drama vent-up trauma unfinished unblemished tough to shake so watch me move this weight.

I stay lean and mean

and sell this right here dopamine.

My name is a Danny

I am an addict

My middle name is denial

and I am a professional escape artist.

Cauã and Dessalines

Trauma is being unheard and unseen

There is a fire deep within me.

Beyond the bookshelves, the analysis, the penmanship, the comrades & the grand vision, there is a young boy who if left to his own devices, would stay in the streets. He’d rob every tycoon and privileged mansion. He’d dish out every pill, poison, expensive brand-name shoes, purses, Nikes and Victoria’s Secret. Who doesn’t dream of being untouchable? A ghetto great who pulls up with the most beautiful woman on his arm.

It is not about hurting no one else, it is about getting your own. The American way… But of course, you are dishing out damage and pain.

Hustling is capitalism’s bastard offspring. You left us nothing but parade the world in front of us. Watch us make our own bread outta the crumbs you left behind Catapulted to new heights Elevated before my children & peers

Shadow Boxing with fear

Playing possum with the police

Moving forward on tomato cans and bleeders.

The South Bronx burns deep within me.

Once you get a taste of that high. It is Irreplaceable. Just to stack up money in my pocket. Can’t nobody touch this. Tax free. Instant gratification. From nobodydom to somebodydom in the wink of a transaction. Finally, I don’t have to listen to no one’s stories about their new job or financial success. I can finally do for me and mine. But it could all be gone in the blink of a rat’s eye…

Sullied money

The ephemeral eraser of envy…

Resentment is the number one offender; but so is poverty.

To catch something…a midnight fisherman…a feeling of invincibility. The night will never end. Fleeting. So, you have to keep making moves. There is no such thing as enough texts, enough bread, enough women, enough drama, enough tragos.

"Enough"

&

Gratitude

are two words

I never heard

in the streets.

We only had the moment

Instant Gratification

and We seized it

with all of our might

and momentum

Left

to pick up the pieces

in a not so distant

future...

You are on your way to this block, already knowing the next move. Your girl’s texts come through forcing a resynthesis of midnight.

It’s endless Unending internalized psychological warfare perpetually perpetuated on to those I love the most ..... my mirror image

The block

Can't stop

Won't stop

Punch forward around the clock

Insomnia breaks night

Stealing

the last breath of tomorrow...

Written on January 3rd, 2016

The Truth about Cuba’s Medical Internationalism

This week, the Trump administration banned any flights to Cuba, except those landing in Havana. In June, the State Department banned cruise ships from visiting Cuba. This latest development follows on the heels of the most recent propaganda offensive against Cuban doctors. This is a teachable moment for those wishing to understand the historic role Cuba medical internationalism has played in the oppressed countries of the world.

The latest, sensationalist anti-Cuba headlines attack the country’s well-known, international medical missions with vague, vulgar allegations. More slander. More propaganda. Nothing new. Not once in the past 60 years, since Cuba’s triumph over neo-colonialism, has the capitalist press pronounced a positive or friendly word about Cuba.

Hellbent on overthrowing a government that represents the 99% of Cuba, the corporate media resorts to outright lying. Progressives the world over must contextualize this latest defamation within the context of the unrelenting U.S. military, economic, diplomatic and media war against the island only ninety miles away from Miami.

What is it that the U.S. fears so much that they spread this misinformation? An International Journal of Health Services published a survey of Cuban international medical missions:

“Since the early 1960s, 28,422 Cuban health workers have worked in 37 Latin American countries, 31,181 in 33 African countries, and 7,986 in 24 Asian countries. Throughout a period of four decades, Cuba sent 67,000 health workers to structural cooperation programs, usually for at least two years, in 94 countries.”

Thousands of Cuban doctors volunteer every year across the most forgotten and exploited countries. In Africa, they are known as “the peaceful Cuban army of doctors in white coats.” What other country in the world has made comparable, selfless sacrifices?

While the U.S. exports F15 jets, deadly, polluting military hardware and more wars of recolonization and destruction, Cuba exports doctors, medical supplies and healthcare.

Cuba’s medical internationalism is, of course. incomprehensible to The Miami Herald, Univision and the gamut of mainstream media outlets who see everything and everyone through the prism of profits. Ignoring the decades-long contributions of Cuba’s medical solidarity, they harp on one supposed informant who alleges that she reported more patients than she saw and invented phony diagnosis. Without any proof, The State Department followed suit, stating: “Profiting from the work of the Cuban doctors has been the decades-long practice of the Castros, and it continues today.”

These propagandistic outfits create sensationalist headlines in hopes of discrediting Cuba’s medical missions and further isolating the island economy. Reuters reported that the U.S. recently blocked the Cuban Health Minister entry to participate in a conference in Washington D.C. These unilateral decisions have nothing to do with medical ethics and everything to do with U.S. geopolitical interests. Every year in September all the countries of the General Assembly gather at the United Nations and vote to end the blockade against Cuba. Yet, the U.S. vetoes the popular vote even though they have no support, except from Israel. The vote this year was 189 countries against the blockade and two for it. The U.S. employs a similar strategy against Venezuela, Iran, North Korea and any country that dares to exist outside of their sphere of influence. The unity of oppressed countries is what the U.S. ruling class most fears.

Historically, Cuba’s global contributions have not just been in the medical field. Cuba: An African Odyssey documents how half a million Cuban troops served in Africa’s Liberation Wars from Portuguese, French and other Western Countries’ Colonialism. Again, how incomprehensible this all must be to a military whose raison d’etre is to invade, occupy and pillage resource-rich countries i.e. Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and beyond…

Trump — the CEO of the United States of America — is worth over $3 billion dollars. This would never be allowed in Cuba. Trump’s wealth — swindled from his massive real estate holdings — would be seized and redistributed in Cuba to meet everyday people’s educational, medical and transportation needs. This is why the elites of the U.S. will never forgive Cuba. The U.S.’s blockade has done everything to prevent Americans from visiting the island of eleven million and seeing Cuba for themselves. For decades, harsh laws have threatened to jail any American citizen for ten years and or fine them $100,000 for the “crime” of visiting Cuba. While the Obama administration sought to slightly lessen the noose around Cuba’s neck, Trump has promised to tighten it again. The Bigot in Chief has promised to put an end to the Cuban system once he has finished with Venezuela and Nicaragua.

The critical viewer is not fooled: the latest media, diplomatic, economic and military aggression is the latest phase of a wider campaign to overthrow the Cuban Revolution.

Yugoslavia: A Blueprint for Imperialist Partition and Recolonization

I left Croatia to the north and mounted a bus that wound through the misty, majestic mountains of Bosnia into Sarajevo. As the sun rose over the historic valley, I saw pock-marked homes that still lay demolished, twenty years after the war ended. Here I was, at the interface of great religions and empires, where a young Bosnian nationalist’s assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand, the maximum representative of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, supposedly sparked WWI. But no individual sparks a war. Wars are politics by other means with major powers vying for control of wealth, markets and other geo-political interests. Respiring centuries of history, I began to question and dig in order to understand what brought war to this wondrous sacred land, once known as Yugoslavia, beginning in 1991 and continuing through 1999.

NATO’s War

Twenty years ago, the forces of NATO, led by the United States and Germany, waged war on the people of Serbia. Over the course of 78 days in 1999 — from March 24th to June 10th — NATO dropped 79,000 tons of bombs and 10,000 cruise missiles on Serbia, causing enormous casualties to the civilian population and extensive damage to the economic infrastructure. This was the culmination of the dismemberment of a global colossus, Yugoslavia was no more. Now, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Macedonia and now Kosovo were left to fend for themselves. 50,000 U.S. and NATO troops now moved unimpeded into Kosovo, an area that was southern Yugoslavia.

The corporate media spoon-fed the world a false, facile explanation to justify its all-out assault on the sovereignty of the Balkan nations. They focused solely on what they portrayed as the sudden resurgence of ancient bloodletting feuds among the nations of Yugoslavia, select victimhood and the need for the West to come to the rescue. There is no question that narrow nationalism and local misleadership led to massive bloodletting. The BBC documentary, “The Death of Yugoslavia” methodically traces the slow disintegration of Yugoslavia. However, these were internationalized civil wars, just like Libya and Syria today. The mainstream media repeated the “ancient nationalist sparring” perspective ad nauseam because it reinforced a grim, generalized view that the “victimized” nations within Yugoslavia “needed” Western intervention. This article revisits the Western military powers’ flagrant violation of international law and what lessons anti-imperialists can draw today from the dismemberment of Yugoslavia.

Torn Apart at the Seams

The victors of WWII hoped to sink their fangs into the Balkans since 1946 when the Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia, led by Marshal Josep “Tito” Broz, defeated the Nazis and established the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The son of a Croat father and Slovenian mother, Tito grew up in deep poverty. He became a metal worker and worked for the German Benz car factory. He rose to the leadership of the labor movement, the Partisan army, the revolutionary party and the workers’ state. What made him and the other partisans a special leadership was their ability to unite the different nationalities of Yugoslavia behind the idea of a strong, peaceful multinational state.

The profiteers of the West knew that it was only the Yugoslavian fortress — the idea of a strong, united people personified in the principled leadership of The League of Communists of Yugoslavia — that protected the individual nations —Slovenia, Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and ethnic Albanians who were spread throughout the south — from complete re-penetration by foreign capital. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990 and the socialist camp left the door wide open for Western maneuvers to rip apart one of the few self-determining and socialist countries left on the global map.

Yugoslavia’s demise was hastened by outside interference which dictated that this centrifugal force had to be smashed. Behind the scenes, foreign meddling stoked the flames of ethnic hatred by encouraging the independence of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Macedonia and Kosovo.

In 1991, President George Bush and Congress passed the Foreign Operations Appropriations Bill which cut off loans, credit and trade for any part of Yugoslavia that did not declare its independence. Italy promised Montenegro $40 billion in “aid” if it went independent. Germany coddled the Croatian bourgeoisie, enticing them with investment promises. Kosovo was built up as “the capital of the Pentagon in the Balkans” with U.S. Turkish and Albanian joint forces trained and supported the Kosovo independence movement.[1] Meanwhile, Serbia — the most stubbornly independent republic with the deepest ties to non-Western countries, namely Russia — was subjected to sanctions. As a result, the per capita Serbian income was reduced from $3,000 in 1990 to $700 by 1993.

Yugoslavia & a Correct Evaluation of the National Question

The Yugoslavian economy was not classically socialist but it retained features of a planned economy unacceptable to international high-finance.

Slobodan Milošević, the President of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and his leadership became imperialism’s principle obstacle. The other nationalities had brokered deals with their imperialist sponsors, retreated into their own fiefdoms and were open for business. Milošević had to go. Consequently, he became the latest anti-Christ needed to validate the unleashing of a full-scale NATO war. Milošević’s intransigence before NATO was his true crime, far worse in the eyes of the West than the rapes, murders and massacres that occurred under his command and the command of every warring party in the 1991-92 conflict that saw over 200,000 killed and four million displaced. The war for Kosovo in 1998 and 1999 saw similar atrocities committed by both the Serbians and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). Noam Chomsky’s book Manufacturing Consent explains why some victims are worthy while others are not.

Only under socialism was it possible to unite all of the nationalities on the basis of equality and common ownership of property. Serious efforts were made through Affirmative Action programs to invest in the development of the historically more underdeveloped southern regions of Bosnia, Montenegro and Kosovo. The League of Communists of Yugoslavia in each republic forbid their leadership and rank-and-file from having a nationalist orientation. The ideals of internationalism and working-class unity were the bedrocks of the entire social system. For a more-in-depth evaluation of Yugoslavia’s history, economy and dedication to equality, Richard Becker’s article is insightful.

Socialists respect the right of every oppressed nation to self-determination. But we oppose those forces who claim to speak in the name of a nation but are really acting in conjunction with U.S. imperialism.

The separatist claims of the NATO-supported, fascist Kosovo Liberation Army were in reality against the interests of the working class of all nations. As Kosovo — a region rich with mineral wealth — was pried away from Serbia, Serbia was subjected to a 78-day bombing spree. Gregory Elich — author of Killing Democracy: CIA and Pentagon Operations in the Post-Soviet Period — detailed NATO’s intentional targeting of auto factories, civilian infrastructure, and the Chinese embassy.

Kosovo became the host of Camp Bondsteel the U.S. and NATO’s largest base in the Balkans where 7,000 foreign troops continue, to this day, to oversee the colonial project. U.S. and NATO troops parade around George Bush Street, Bill Clinton Boulevard, Woodrow Wilson Street in Pristina, Prizren and the rest of Kosovo as heroes. Kosovo celebrates July 4th as if it were a national holiday. On the side of one of Pristina’s largest skyscrapers, a massive banner thanks the U.S. for Kosovo’s freedom. A New York Times article outlined the business interests that U.S generals and officials, like Madeline Albright and Wesley K. Clark pursued in Kosovo post-war. Kellogg, Brown and Root, KBR Inc. — a military subsidiary of Halliburton — received the massive contract to build and supply the base.

None of this foreign intervention negates the Kosovo Albanians’ legitimate gripes and right to greater sovereignty. The key point is the U.S. ruling class manipulated these genuine calls for greater autonomy in order to smash the Yugoslavian fortress.

In the words of capitalist ideologue Thomas Friedman; “The hidden hand of the market will never work without the hidden fist — McDonalds cannot flourish without McDonnell Douglas, the designer of the F-15.”[2] Kosovo — like Tibet, South Sudan, & the Kurds of Iraq (but not Turkey) offer an example of imperialism’s sinister manipulation of the question of national liberation.

Srebrenica: Sorting through the propaganda

Nazi propagandist Joseph Gobbles infamously said: “A lie repeated 1,000 times becomes the truth.” One-sided reporting simultaneously freed the U.S. proxy forces of blame while vilifying any impediments to their underlying designs. The most glaring example in the case of Yugoslavia was what the West called “the Srebrenica genocide.”

There is no question that the segregation of Muslims and the siege of the majority Muslim, Bosnian town of Srebrenica was horrific. But was it any more or less grisly than the Croatian ethnic cleansing of Serbian families in the Krajina region or the massacring of Serbs by Muslim warlord Naser Oric in the days leading up to the Srebrenica massacre? All sides committed mass murder, rape and other war crimes. Imperialism needed Srebrenica and the “pure” victimhood of Bosnia’s Muslims to justify their wanton destruction of the infrastructure and economy of Serbia. Scholars Michael Parenti and Diana Johnstone, among others, painstakingly documented the one-sided coverage to guilt trip the Western public into supporting the NATO war. As we have seen in Iraq, Libya and Syria, the pro-imperialist media is very adept at feigning concern for human rights. The U.S.’s wars of the 21st century are justified under the guise of “humanitarianism.”

Lessons Learned

Studying and understanding the dynamics of the dismemberment of Yugoslavia teaches us valuable lessons that we can apply to the empire’s ongoing wars of conquest across the world today. As the godfather of all war criminals Henry Kissinger reminds us, the U.S. “has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests.”

Although the ruling class has whipped up islamophobia to justify its imperial adventures in Afghanistan, Palestine and beyond and to rationalize the repression of dissent here at home, imperialism is not anti-Muslim across the board. The ruling class is far too cunning and “globalist” for this. In the case of Yugoslavia, one of their main proxies was the Muslim president of Bosnia, Alija Izetbegovic and the terrorist outfit, the Kosovo Liberation Army.

Izetbegovic served three years in jail for his support of the Nazi occupation of Croatia during WWII and later became an extremist advocate of Sharia law. Today it is common knowledge that the U.S. conspired with extremist, jihadist forces from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Albania and beyond to wage their proxy war in Bosnia. Professor Peter Dale Scott documents the West’s use of al-Qaida in Bosnia. He argues that the training of some KLA units in terrorist camps run by Osama bin Laden followed a long pattern also used by National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski in Afghanistan in 1979 to defeat the secular government of President Najibullah and the Progressive Democratic Party of Afghanistan. Not a word was uttered against the honor of the Muslim Bosnians and Kosovars because they were the “good guys” in this conflict. They needed a pure victim and a totally evil aggressor (Serbia) led by Satan himself (Milošević).

“Moral Combat: NATO at War” is one entry point into understanding the West’s relationship with the KLA. Tough the KLA commanders openly admitted their strategy was terrorism directed at the Yugoslavian police forces and the Serbian civilian population, the KLA could do no wrong in the eyes of their backers.

Through think tanks, academic conferences, professional analysts and paid experts, the warmongers constantly monitor dynamic situations. They shift alliances according to their interests. Imperialism has proven that it will renege on old partnerships and create new ones according to the moment.

It is enough to remember that “bad guys” such as Manuel Noriega, Saddam Hussein and Osama Bin Laden were all once stooges of the U.S., when the forces they oversaw did the U.S.’s bidding. When it no longer served their interests to support them, the empire turned on them and converted them into the latest boogeyman (i.e. ISIS). Their crimes and human rights records then became convenient excuses to bomb, invade and occupy Panama, Iraq and Afghanistan which were all steps in the recolonization of these regions.

When the non-aligned Yugoslavia functioned as a buffer zone between the Soviet Union and the U.S. in the Global Class War, the IMF and the European banks were content to lend it money, drive another wedge through the idea of Soviet-Yugoslavian unity and keep it —even if only partially — in their sphere of influence.[3] With the rise of the unipolar world, this calculation changed. The U.S. and EU countries did not stop their war drive until the country was completely under its boot again.

Yugo-Nostalgia

According to studies by historians and sociologists, a high percentage of people today — spanning across the different nationalities — yearn for the unity and social stability guaranteed in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[4]

From Zagreb to Sarajevo to Niš, I found responses consistent with this sense of Yugo-nostalgia. Many citizens of the former Yugoslavia bemoaned the stripping away of people’s right to health care, a home, a university education, a job and social peace — and the concomitant privatization of these services. In their opinion, these maneuvers represented the “thirdworldization” of the Balkans, a return to a position of servitude they had valiantly overcome. According to an article in The Economist entitled “Balkan’s Economies, Mostly Miserable,” 23% of Serbian workers are unemployed today and this number climbs to the 50% mark for younger workers. These statistics are representative of the struggles of the different nationalities of the region to make ends meet and resist the globalization forced upon them by NATO bombs.

A Template for Imperialist Wars Today and Tomorrow

Karl Marx said that “History repeats itself first as tragedy then as farce.” We can see the same dynamics of the Yugoslavian situation playing out again in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria and beyond, as the American public is duped again.

The mainstream media — which functions as the de facto spokesperson of the State Department — does not get it wrong. A key part of anti-imperialists’ training — dating back to the Zimmerwald Conference when socialists maintained that WWI was not fought in the interests of working people — is to read beyond the headlines and stay principled when imperialism goes into war drive. When our class enemies beat the war drums and pretend to appeal to Americans’ human compassion — as they do with every U.S. invasion — it is necessary to decipher what the empire’s true interests are. No matter how relentless, sensationalist and patriotic the barrage of propaganda, it is unacceptable to line up shoulder to shoulder as our oppressors at home relentlessly demonize inconvenient nationalist forces abroad. It is important to return to Malcolm X’s formulation: “If you’re not careful, the newspapers will have you hating the people who are being oppressed, and loving the people who are doing the oppressing.” Our defense of a nation’s right to defend themselves vis-à-vis foreign domination is not a blanket endorsement of their social systems. Surely every social system has its flaw and challenges, but this is no justification to dismantle the central state of the aforementioned countries.

As the billionaires run out of new markets to conquer, they are seeking to expand. China, Russian and the other strong, independent nations are demonized because they have resisted deeper penetration. The wars of the 21st century will be ignited along these lines and will come packaged in human rights rhetoric. Any nation who resists capitalist re-enslavement — Zimbabwe, the Bolivarian camp in Latin America, eastern Ukraine, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Cuba and the DPRK — is in the crosshairs. The hundreds of thousands of refugees who seek to cross the Mediterranean Sea into Europe are the very victims of these recolonization efforts. They have been defuturized by U.S./EU proxy wars. While the corporate media outlets lament the plight of the refugees, they do not utter an honest word about the source of this human conflagration. Libya, Syria, Yemen, Iraq and Afghanistan are today’s Yugoslavia. The greatest solidarity we can render to imperialism’s millions of victims is by challenging its power right here in the belly of the beast! Until then, in the words of the prophet of peace, Bob Marley, “Everywhere is war.”

[1] Dakovic, Mirko. The Center for Peace in the Balkans. March 22, 2001. “Destabilizing the Balkans: U.S. & Albanian Defense Cooperation in the 1990s.”

[2] Cited in the New York Times, March 28th 1999.

[3] The Soviet leadership was to blame for failing to unite with Yugoslavia on an anti-imperialist basis. This was due to the fact that post WWII, the Soviet Union agreed with the U.S. and Britain to divide up Southern Europe between the three powers, with Greece and Yugoslavia falling into the U.S./British sphere of influence and Bulgaria and Hungary falling into the Soviet orbit. Stalin then unjustifiably expelled Yugoslavia from the Socialist Camp at 1948 Cominform meeting accusing the Yugoslavs, among other charges, of “Nationalism; and, ‘counter-revolutionary Trotskyism.” This was a huge gift to imperialism. With his back against the wall, Tito soon after moved into a military alliance with NATO. He was a central figure along with Nasser, Sukarno, Nehru and Nkrumah in the non-aligned Bandung Conference of 1955, which objectively became drew the newly decolonizing countries away from the Soviet-led socialist camp.

[4] Several studies are cited in Titostalgia: A Study in Nostalgia for Josep Broz by Mitja Velikonja.

The Brockton High 1996 Basketball and Football Team, 20 Years Later

I left Brockton, Massachusetts in 1996 to study and play basketball in New York City. I lost touch with most of my old teammates. Last night we caught up at Owen O’Leary’s over some beers and burgers. It is amazing how things have shifted in 20 years! I jotted down some of my impressions, changing everyone’s name to protect their privacy.

Hakeem was All-American. He was the type of athlete who could drink and smoke all night and then set national records the next morning. When he played against New Bedford, no one thought he was even going to show up for the game. The coach sent a car looking for him. The assistant found him just in time. Without even stretching, he ran for 409 yards and 6 touchdowns. With one foot in the streets and the other on the gridiron, he was always one step from the precipice. He was infamous for shutting down movie theaters. He would come in with his crew then make sure no one else got in unless they paid him for “a second ticket.” He was recruited to be Indiana University’s next great running back. He blew out his knee. A decade later he weighs 350 lbs. After years in the street, he became a foreclosure prevention expert.

Big Glom was Portuguese American. He was one of few English speakers on the soccer team. Even the coach preferred to speak his native Kreolu Kabuverdianu. Glom translated when the referees had to give instructions to Coach Lopez. He did a famous bicycle kick against Durfee. As he did a back flip, he swung his powerful leg around and scored the winning goal. The Brockton faithful exploded into applause and mobbed the field, hoisting Big Glom up on their shoulders like he was Tom Brady. Excelling at soccer, Coach Colombo recruited Glom to be the football kicker. He served in the Peace Corps for four years in Peru. He is now an ESL teacher. The other day after an unfortunate shooting, he wrote on Facebook: “Deeply saddened. 14 years teaching, 6 students murdered.”

Matt was the basketball center behind me. He became a guidance counselor at South Junior High. 6’9” and committed to his students’ progress, Matt is an impressive role model for the students.

Joshua Johnson gravitated between the legal and illegal realm. He was the victim of a drive-by shooting on Route 24. Some local bandits shot up his car and his intestines to send a message. He has lived his life as a half-vegetable since.

Bobby G was a 230 lb. fullback. Today he is a 460 lb. double fullback. He is still sturdy but not as strong. He became an actor and hustled on the side. They called him Goose because of his fondness for Grey Goose and other types of vodka.

Pat and Mark never had good attitudes but they were definitely both great athletes. Ironically, they are coaches today of the teams we once played on. Dealing with 15 and 16-year-old angst, they probably have a different perspective on what they were like at that age.

Wheeze was never an athlete per se; Wheeze was an enforcer. The coaches kept him around for pure intimidation. If there was a scuffle, he tackled the opposing players before a punch could even be thrown. He was kicked out of so many games, there was a debate if he could come back for the playoffs. To get pumped up before games he listened to Rage Against the Machine and went into a trance, bobbing his head up-and-down to his own rhythm. He was too crazy to feel fear. Today he is an artist. He paints and draws expressive canvases. Sometimes he disappears for a week on his bicycle, coming back when he feels he is ready to deal with people again. He lives by Pedro Pietri’s motto: “Sometimes you have to lose yourself for a while in order to find yourself.”

Tyrone was another world-class athlete. He won dunk contests blindfolded. He was a quarterback at Syracuse. He was struggling for a while with unemployment. He entered the Investment Banking world before settling as a representative of a sports community. He said he has not moved to even shoot a hoop or go for a run in six years.

Eastside Willie Nice is washed up. He has 12 kids that he recognizes and a few others that he says are “out and about.” Wearing a gold chain over a burnt-out frame, he is a shadow of his former self. He was famous for taking three point shots three or four steps behind the three-point line. Coach Victor Ortiz hated him but never hated the 30 points he poured in on any given night. Today he collects social security for a “back injury.” He uses social media to harass and gawk at women. Like his father, he became a pimp. He is proud two of his daughters became strippers. He pimps out one of his kids’ mothers to Central American laborers for $50. His twitter feed offers instructions about how to treat “hoes.” He was banned from Facebook. It made me wonder about the social and family forces that create misogynists.

His older brother’s name was Z for Zaaron. He was the only other white kid that played basketball with us growing up. But with a name like Zaaron and his street demeanor, no one believed Z was white. If someone called him Larry Bird or the Hick from French Lick, it was an automatic fist fight. Calling him Bob Cousy was even worse. Zaaron had it rough. His mother was a bad addict who tried to kill him over and over. He must have had more lives than Fidel Castro. He set up booby traps in his house for would-be invaders. We weren’t sure if suffered from paranoia or Brocktonnoia. He flirted with drug-dealing lifestyle but taking into consideration how it destroyed his family, he backed off. He disappeared from public view and resurfaced in Alabama. He went to night classes and got his GED. He won a engineering scholarship to Michigan State, graduating with honors. He runs a computer company based out of Argentina and Guatemala.

Moose was a Cape Verdean force to be reckoned with. He had the most massive biceps and natural afro anyone had ever seen. He had a unique hustle. He would take old bikes on their last leg and ride them to the suburbs. He then made his way back to Brockton on brand new ten speeds and mountain bikes. He flipped them before repeating the endeavor. Moose became a professional football player in Canada. Like most football careers, it only lasted a few years. He became a bouncer.

Manny owns a barbershop. He was a point guard who was fleet of foot and a good conversationalist. He hailed from a long line of pretty boy point guards and players. They say his old man was in his 60’s and still cheated and had women on the side. Manny was on that very path.

Paul came to Brockton as a hustler and left Brockton as a hustler. I’ll never forget when our coach Victor Ortiz sat him on the bench and slapped him in the middle of a game because he didn’t run the right play. That shocked and hurt all of us. We all said if that was us we would have done this and that but the truth was none of us did anything. Paul caught a murder one rap on Main St. He did federal time until he was deported to back to his neighborhood Atchadinha in Praia, Cape Verde.

Conner fought if you looked at him wrong. Conner fought if he though you said something about him. Conner fought & fought & fought. Everyone just discarded him as crazy. But no coach complained about how tough he was on the football field. That was his only relief. Many of us judged him but did any of us know his story. When he was a toddler, his mother intentionally burnt him with a iron to punish him. When Conner was three, she made him eat out of a litter box. When she was in a bad mood, she wouldn’t let him leave his room to go the bathroom. She “played games,” making him drink his own urine and eat his own feces. Most of us can’t understand such unconscionable acts. But when you go deeper into her story, you realize this is what she went through a generation before when she was robbed of her childhood. It is so easy to point a finger at the beasts but what about the social bestiality that called them into existence? For 47 long years, Collin hated his mother. It was only last week that he took a step back and realized why he was always fighting. He started to go to different anonymous survivor groups so that he wouldn’t pass the savagery onto his three daughters.

Edgar De Barros was the craziest and calmest of us all. I remember long conversations in the red caefteria about life and where we would be one day. I also remember pulling his legs back as he lunged into an office at the local YMCA trying to stab Sean Pearson over a disagreement on the basketball court. We had hid Sean in there to try to save his life. Edgar was not deterred. He punched and stabbed out a hole to climb through the window. We continued to pull him back in order to prevent a stabbing. This was 1995. But Edgar matured and started a family just as he had imagined he would in the red cafeteria. Just when things were settling into place, he died in a mountain-climbing accident with his father in their homeland of Cape Verde.

Gary is a family man who works for an insurance company in Boston. He is an assistant coach of the Basketball team. I tried to make conversation but we couldn’t find much to talk about besides the Patriots and Celtics.

Kevin had the potential to play pro. But his sophomore year as a shooting guard at Texas A&M he blew out his knee. Overnight, Kevin went from being a dreamer to a schemer. He transferred colleges after some academic problems and getting caught selling. 20 years later, stuck in Brockton, he was still bitter about his fortunes.

Jeff ended up at Florida State and is a corporate banker with a home in Brookline, a suburb of Boston. Never much of his own man, his wife makes his decisions for him.

Kendrick wanders through the Westgate projects getting high and talking to himself. He was supposed to take antipsychotic meds but preferred to self-medicate with weed.

G-man was a natural born hustler who came up and blew it all. He was a cocaine supplier who got out of the game in time to cross over to mail-carrying. Today he is a family man who everyday resists the impulse to hit the streets again.

Daquan — the goofiest of all of us — became a Brockton cop. After all the trash he talked about being in the streets and hating the police, it was tough to believe the career path he chose.

Deshaun pledged to get as far away from Brockton as he could. He didn’t want his kids to see what he saw growing up in a cesspool of heroin and violence against women. He drives for UPS. He is still a great athlete. He moved to a town in New Hampshire that is .06% Black. Before he moved there with his family, it was 0% Black.

These were the stories I could recover. Other former teammates disappeared from public view.

It was great to see old faces and see how people have grown and evolved. I meditated on former friends who got stuck in their surroundings and never managed to move beyond them. There were some gung-ho, dog-eat-dog, hate-the-Iraqi, blame-and-hang-the-victim type comments floating around that I couldn’t really respond to at the reunion. Beyond that, it was good time.

I wanted to go deeper at some points with the old crew about growing up and the challenges. Whose old man was around and whose had run away? Whose mother was strung out and whose was at home? Whose family had succumbed to addiction & violence and whose had escaped?

So many questions. So few answers. I will pose at our next reunion in twenty years.

And that was our night grabbing beers at Owen O’Leary’s.

A Giant Social Paradox: China in 2017

To see China through western eyes is to misunderstand China. These are some of my impressions after visiting Beijing and Shanghai this past summer and studying China’s modern revolutionary history over the course of the past two decades as a member and leader of the U.S. socialist movement. I have provided links to critical background materials for those who wish to understand China in more depth.

- The 1949 Chinese Revolution was a monumental event not just for the masses of poor peasants and workers in China but throughout the world. One of the great event of the 20th century, the Chinese revolution raised hundreds of millions of people out of destitution. The last became first and the Western-backed old ruling class was sent scampering to Taiwan where they planned for the overthrow of the revolution. In the 1950’s, ruling circles in the West obsessed over “Who lost China?” Students of political science and revolution the world over have a responsibility to study the lessons and challenges of the Chinese Revolution.

- William Hinton’s Fanshen: A Documentary of Revolution in a Chinese Village is a snapshot of how class relations shifted. Fanshen (the word means to turn over and start anew) documents how peasant democracy and a planned economy under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) played out in one village. The American farmer and writer captured the self-sacrificing spirit behind the CCP cadre who mobilized the sleeping giant, the Chinese peasantry: “I often thought what hardship it must be for such a woman to live the life of a spartan revolutionary cadre in the bleak North China countryside… Yet she seemed to pay no attention whatsoever to cold, fatigue, lice, fleas, coarse food, or the wooden planks that served as her bed. For her this was all a part of ‘going to the people’ who alone, once they were mobilized, could build the new China of which she dreamed.”

- Post-1949 Red China was a beacon of hope for all oppressed people. China’s foreign policy was one of principled internationalism supporting colonial people’s struggles for self-determination across the globe. Robin Kelly’s article Black like Mao: Red China and Black Revolution explores what China meant to oppressed people here in the belly of the beast.

- The 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution was “a revolution within the revolution.” 50 years later, the Cultural Revolution still strikes fear into the capitalist class. Mao’s orders to the everyday workers, peasants and students “to storm the headquarters” meant the temporary crushing of capitalist and bureaucratic forces that threatened to creep back into the driver’s seat of the Chinese state.

The Cultural Revolution is a stern reminder that our class, the working-class, is not the only social class that can be repressed. Elite circles in the US have seized every opportunity, 50 years after the fact, to heap slander on this momentous chapter in world revolutionary history. Our responsibility is to rescue the legacy of the Cultural Revolution and set the record straight.

The Cultural Revolution is a stern reminder that our class, the working-class, is not the only social class that can be repressed. Elite circles in the US have seized every opportunity, 50 years after the fact, to heap slander on this momentous chapter in world revolutionary history. Our responsibility is to rescue the legacy of the Cultural Revolution and set the record straight. - From the perspective of the struggle against bureaucracy and class inequality, the Cultural Revolution was the high point of the Chinese Revolution. It was also exhausting and divisive. Struggle sessions, constant denunciations and mobilizations staved off internal enemies but the excesses and extremes resulted in the political pendulum swinging back to the right. The mysterious death of Lin Biao, the death of Chou En Lai, Mao Zedong’s development of Parkinson’s disease and the swift repression of his successors (the left-wing of the CCP, known by their detractors as the “Gang of Four”) represented the end of principled communist leadership and the consolidation of the capitalist roaders, personified in the leadership of Deng Xiaoping.

- The secret 1972 visit of Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon—the genocidaires of Indochina, Indonesia, the Dominican Republic, the Congo etc.—represented a sharp right turn in Chinese foreign policy and a knock-out blow to the vision of Soviet-Vietnamese-Chinese-Third world unity. The CCP leadership lost sight of the true enemy and succumbed to historic rivalries and chauvinism. These tensions became so pronounced that Vietnam invaded Cambodia in self-defense in 1979. China then unjustifiably invaded Vietnam. Instead of focusing on a common unity, China turned on a sister socialist state. The brunt of the blame must also fall upon the Soviets who chose accommodation with imperialism before international solidarity. China then beat the Soviets to the punch by shifting towards the US government. The Sino-Soviet split represented the complete collapse of the Marxist principle of internationalism. This is the largest blemish on Mao’s principled pedigree as a leading historical and global revolutionary spokesperson. Sam Marcy’s China: the struggle within and China: the suppression of the left, published by Worker’s World in the 1970’s and 1980’s, offers a profound evaluation of the struggles within the summits of Chinese leadership and their turn to the right.

- China’s reactionary foreign policy based on narrow nationalist interests played out in disastrous ways. As a result of seeing the Soviet Union as a “social imperialist” (an incorrect, non-Marxist formulation) and humanity’s number one enemy, China supported Pinochet in Chile, UNITA in Angola and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. China’s misleadership threw a purported 600 Maoist parties, who had been a tail to the CCP’s kite, into disarray around the world. With their center of gravity removed, the Maoist movement in the West crumbled and never recovered. Today in the Philipines, Nepal, India and beyond there is a powerful Maoist movement that controls large swaths of these countries.

- Like Mikhail Gorbachev, Deng Xiaoping was a darling of the West. Still, despite opening up China to foreign capital, he did not move at the pace that imperialism insisted upon. The West worked with Deng Xiaoping but the moment there was an anti-CCP movement within China that US intelligence calculated could undermine and overthrow the revolution, the US latched on. The 1989 seven-week long Tiananmen Square protest represented this opportunity for the US; they saw a potential rallying point for the overthrow of a system of centralized planning. The west cried crocodile tears for what they presented as defenseless students massacred by CCP tanks. The reality on the ground was quite different; there was repression but there were also pitched battles resulting in the death of Red Army soldiers. The Tiananmen Square students held up Gorbachev and the Statue of Liberty as beacons of “democracy” and the “free market,” revealing their vision for China’s future.

- Understanding the US’s approach to regime change in Libya and Syria offers clarity on its strategy towards China. The US government engaged with Gaddafi and Assad even though the two leaders maintained a sense of economic nationalism combined with neoliberalism. As soon as Western intelligence detected a small protest movement within (including elements of al-Qaeda and ISIS) that they could back, they switched from a strategy of working with Pan-Arabists to one of regime change. This is how we should understand US foreign policy towards China today, one of toleration until the moment is ripe for regime change.

- Chinese foreign policy today is based on what is good for the Chinese state, not proletarian internationalism. China’s expansion, from Ecuador to Angola, represents an important counterweight to US capital. This interactive New York Times map offers a sense of the emergence of China as a global rival to the U.S. China still seeks surplus and profits but on preferential terms for exploited countries compared to its capitalist rivals. This is preferable for exploited countries seeking to emerge from under the yoke of a unipolar world. The bourgeois media constantly attacks China’s foreign investment because “China invests in countries with poor human rights records.” What a joke! Perched atop a pulpit of bones, the imperialists pretend to be guided by a moral compass as they squeeze profits from every corner of the earth.

- Ecuador is one example of left-leaning, anti-imperialist Bolivarian state weaning itself off of Western debt and dependency. China’s massive investments in Ecuador, Venezuela and pre-Macri Argentina ensured that Western banks could not completely isolate and suffocate the Bolivarian nations’ growth. Washington’s meddling in the region aims to thwart the Bolivarian alliance. Zimbabwe—Africa’s Venezuela so to speak—receives 82% of its foreign investment from China.

- It would also be naïve to overlook the predatory nature of China’s capital abroad. There are two centers of power within China—the CCP and independent Chinese businesses. When left uncontrolled abroad, Chinese capital has proven itself capable of functioning like imperialist capital. The short documentary China’s African Takeover examines Chinese mineral extraction in Zambia and the Congo, providing evidence of the reality that there is a bi-polar Chinese system.

- Red China no longer exists. China today is a mixed bag, a half-way house between capitalism and socialism. The state-steered market develops a domestic and foreign capital in a planned and proportionate way. Socialism with Chinese characteristics means that the government supervises the market and resource allocation. This remains unforgivable from the point of view of China’s detractors and would-be neo-colonizers.

- Trump’s demonization of China is dangerous and faulty. It is true that much of the West’s manufacturing has set up shop in China where they can pay a fraction of the wages they paid in Chicago, LA or Cleveland. What Trump fails to mention however in his jingoistic crusade is that the US multinationals are primarily to blame for the deindustrialization and unemployment that afflict the U.S. Chinese and US capital is entangled; large sections of the US capitalist class benefit from trade with and exploitation of the Chinese labor force. Trump’s promises to restore jobs to the Rust Belt cities will prove empty because for-profit corporations will not return to the US because of some loyalty to American workers. As more workers (especially white workers infected by centuries of racism who voted for Trump) wake up to this reality, there will be large opportunities to shift consciousness to the left across the US.

- To the extent that the U.S. fears China, they fear both a capitalist global competitor, specifically in Asia, and an economy that is still state planned. The extent to which the New York Times, the Washington Post and other US foreign policy establishment mouthpieces critique China and warn of the Chinese menace in the South China Sea reflects their active fear of China’s emergence as a rival economic pole. Because China retains a great degree of self-determination, the Chinese state incurs the wrath of the “free world’s” press which labels it “totalitarian” and “tyrannical.” Seen through a class lens, what these meaningless labels actually mean is that China still retains some sovereignty. As anti-imperialists, we in the Party for Socialism and Liberation, defend a Workers’ state’s right to defend itself from all forms of hostile foreign encroachment.

- The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) true crime is that is it no push over. The CCP still retains an imprecise monopoly over foreign trade. They partially manage foreign capital and redirect it towards the good of China. When the US labels China a dictatorship or a one party system, what they really mean is the CCP is an arbiter of foreign capital. For example, the Chinese firewall, the blocking of Facebook, google etc., functions as a partial break on imperialist penetration. While the West haughtily accuses of China of being backward and isolated, its internet technology is often superior to that of its Western rivals. The Economist notes that many of the apps we take for granted today in the US, such as Uber or WhatsApp, were in fact inspired by Chinese innovation.

- Because Chinese leadership represents a new potential Pan-Asian unity and a new captain in the Pacific, the US seeks to surround China with hostile neighbors. Obama’s visit to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to sell them weapons for the first time since the US’s “loss” of Saigon and their attempt to use the Philippines as a proxy power (which is no longer realistic with the nationalist Roberto Duterte’s presidency) reflects this encirclement strategy. Front page news story of China’s aggression in the South China Sea over some islets is an attempt to justify what was to be Obama’s highly touted “pivot” towards Asia. However the empire is bogged down in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq and elsewhere, and because there are such deep rifts in US governing circles (ie the intelligence “community” vs Trump), the US has been so far unable to fulfill its plan to isolate China.

- In all of the Pentagon’s reports, China figures as the US’s number one long term concern. John Pilger’s documentary The Coming War on China is helpful to understand who the true aggressor is in the Pacific. China is surrounded by some 600 US military bases. Just in Okinawa, Japan, the US has 50,000 troops, only 400 miles off of China’s coast. China desires peaceful coexistence so it can focus on economic development. Its military spending is defensive versus the US which maintains a vast network over 1,000 foreign bases across the globe. In response to Trump’s pledge to increase the US military budget by $54 billion, China vowed to decrease its military budget.

- China remains focused on economic development and open trade as Trump vacillates between isolationism and aggression. Xi Jinping is poised to play the role of the anti-Trump and guide China as the undisputed economic powerhouse of the Pacific. In an ironic historical twist, the CCP is presenting itself as the global defender of free trade. In response to Trump’s anti-globalist posture, Xi Jinping promised another $75 billion of Chinese investment in the pacific.

- Goldman Sachs estimates that the Chinese economy will catch up to the US by 2025 and by 2050 it will be twice its size.

As the capitalist camp has experienced recessions and crisis, industrial production is booming in China. China’s industrial production is 150% higher than the U.S. As industrial production sank in the US and Japan in 2009, it rose 7.3% in China. With decades of centralized planning, under its belt China is poised to outrace its capitalist competitors whose economies are based on the anarchy of the market. For these and many other reasons, imperialism fears that “the 21st century is the Chinese century.”

As the capitalist camp has experienced recessions and crisis, industrial production is booming in China. China’s industrial production is 150% higher than the U.S. As industrial production sank in the US and Japan in 2009, it rose 7.3% in China. With decades of centralized planning, under its belt China is poised to outrace its capitalist competitors whose economies are based on the anarchy of the market. For these and many other reasons, imperialism fears that “the 21st century is the Chinese century.” - The economic basis exists for a transition back to a more egalitarian socialism in China. However, there does not appear to be a strong or vocal tendency within the 90 million-strong Chinese Communist Party that defends a dictatorship of the workers at the present moment. China has more industrial workers than all of the capitalist countries combined. There are big trade union struggles in China. Here within lies the kernel of a potential united workers’ fightback movement against a bureaucracy committed to “market socialism.”

- The rise of China’s mega metropolises has come at the expense of the peasantry. China has rural-urban inequality that mirrors the divide between what the mainstream media calls the “first world” and “third world.” In this sense, China’s interior is a massive exploited country with a line of New York Cities dotting its east coast. The reality is one of uneven development. Remittances, accounting for more than what the provinces themselves produce, keep many families in the countryside afloat.

- There is no unified peasantry like there was under the CCP during the epic-making Long March, the 1949 revolution and the 1966 Cultural Revolution.

The peasantry has been engaged in sporadic local uprisings against the Chinese state but has no unified national approach to organizing. Many in the villages see themselves as exploited and neglected. Will the Boat Sink the Water? The Life of China’s Peasants is a thorough exploration of the class inequality that persists in today’s China. The book was only available outside of China or photocopied and sold in the street. Its authors Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao document bureaucratic abuses of the peasantry of Anhui province and the impunity enjoyed by low-level party opportunists. According to Guidi and Chuntao, many local CCP “cadre” are not guided by revolutionary principles but by careerism. The peasantry is overtaxed and there are ongoing mobilizations against local petty tyranny. The CCP claims to have investigated these allegations and partially addressed peasant concerns.

The peasantry has been engaged in sporadic local uprisings against the Chinese state but has no unified national approach to organizing. Many in the villages see themselves as exploited and neglected. Will the Boat Sink the Water? The Life of China’s Peasants is a thorough exploration of the class inequality that persists in today’s China. The book was only available outside of China or photocopied and sold in the street. Its authors Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao document bureaucratic abuses of the peasantry of Anhui province and the impunity enjoyed by low-level party opportunists. According to Guidi and Chuntao, many local CCP “cadre” are not guided by revolutionary principles but by careerism. The peasantry is overtaxed and there are ongoing mobilizations against local petty tyranny. The CCP claims to have investigated these allegations and partially addressed peasant concerns. - The general superstructure of China today is devoid of revolutionary enthusiasm. In Cuba, the ruling class makes an active effort to create billboards, school curriculum, television programs and general propaganda to promote the cause of international solidarity and world revolution. In the Eastern Chinese sea board, there is nothing of the sort. Every corporation—from Versace to Starbucks to Kentucky Fried Chicken—enjoys free reign across China. To the extent that Cuba had to institute economic reforms in order to survive in a hostile capitalist world, the Cuban leadership correctly identified them as necessary retreats to survive in a hostile world. The Chinese leadership has adopted faux Marxist rhetoric to justify its capitalist moves. When Cuba found it necessary to introduce foxes into a chickens’ coop, it correctly labeled the foxes and chickens. The CCP confuses foxes and chickens, friends and enemies.

- China is a mammoth social paradox. There was a Hooters a few blocks away from the Communist Youth League office. A museum of propaganda is housed in the basement of tenements buildings where the curators and historians struggle to attract visitors. The state shifted away from the promotion of socialist consciousness in the 1970’s and maintains these museums as artifacts of a bygone era. A Brookings Institute study showed the mixed reactions the Chinese have to Donald Trump. While many Chinese predictably decried his saber-rattling against their country, there were large segments of the population who admired his “business acumen.” How telling in terms of general state of Chinese consciousness today! Various professors I met were flabbergasted at the indifference of many Chinese students, even in comparison to the average U.S. college students! One professor used the term “politically neutered” to describe them, explaining that “with a few exceptions if you ask them for their views on politics, they seem almost aggressively apathetic in their views.” This made the old guard apprehensive about the future of Chinese leadership.

- If Time Square is a monument to capitalism, the shopping centers of Beijing and Shanghai surpass this and are monuments to the future of capitalism. The latest Hurun Wealth Report shows that in 2015 the number of billionaires in China (596) surpassed that of America (537). The richest 1 percent of Chinese families control one-third of all Chinese household assets. This is a level of inequality similar to the U.S. Chan Koonchung’s novel The Fat Years is an underground parody of the lavish lifestyles and corruption that characterizes life at the top in China. Completely turning on Marxist principles, the CCP allows capitalists, billionaires and exploiters (all three terms are interchangeable here) to be members and leaders of the communist party. The CCP has also periodically hands out prison sentences, or even death sentences, to corrupt bureaucrats and capitalists for abusing their power, something unimaginable in the US. Recognizing the drastic effects of pollution and global warming, the CCP has also cut down on carbon emissions. These policies stand in stark contrast to the unrestrained capitalism that Trump is now overseeing.

- The US media has never hesitated to attack General Secretary Xi Jinping. Xi Jinping is the son of two long march veterans. His father was a vice-premier of the CCP in the Mao era. Two of the lynchpins of Xi’s leadership are a relentless campaign against the corruption that crept back into daily life with the introduction of foreign capital and a return to some of the PRC’s and the CCP’s founding ideals. This makes Xi a target of Western propaganda. The New York Review of Books’ article on Xi is one sample of a lengthy, biased attack on CCP leadership.

- Are there a sense of social harmony and a unity of purpose in China today? From my perspective as an outside observer, China stands in stark contrast to the US which is rife with social implosions i.e. the election of the divisive, semi-fascist Trump, school shootings, terrorist threats, racist police terror, state declared emergencies because of drug addiction, etc. In comparison to the divided US ruling class, the CCP plays the role of the one captain directing China in a unified direction. For example, 90% of China’s 1.3 billion plus people identify “racially” as Han. There is a long, complex history to Chinese identity formation but many Chinese does not identify their country as multiracial. Of course, China has its social ills and national divisions (Tibet, the Uighurs, internal migration and exploitation, environmental crises) but some might consider them mild compared to what the US is experiencing.

- The US is long accustomed to seeing itself as the center of the world. China’s development at break-neck speed shows the superiority of a centrally planned system over the free market. In this speech, Guardian columnist Martin Jacques urges a Western audience to humble themselves before the shifting global relations and points towards a Chinese future.

- Our party’s (the Party for Socialism and Liberation) book China: Revolution and Counterrevolution is a deeper consideration of how to understand China, and all of its vicissitudes and contradictions, as anti-imperialists and revolutionaries in the 21st century. Our position, as I have laid out in this document, critiques China’s accommodation with imperialism after 1972 but still defends China vis-à-vis imperialist aggression.