This is an excerpt from The Saints of Santo Domingo, a book that explores the ascendance of the Dominican Republic’s revolutionary movement, the MPD (Movimiento Popular Dominicano) and the state repression that followed. It is a work of non-fiction. Details have been changed to protect the privacy of the real life protagonists.

Whatever you needed, Franklin had it. Guns, a safe house, a bodyguard, money, contacts within the police to tip off the movement, counterintelligence, hitmen, lawyers to defend political prisoners, or CO’s to smuggle letters and books to comrades in prison. His smile was the key to every vault in Villa Altagracia, a municipality of 180,000 just north of the capital. Everywhere he went, he was well-respected and well-loved.

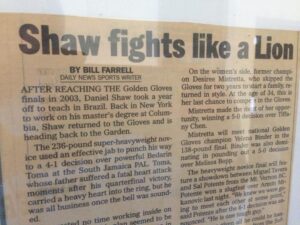

Franklin had a magnetic personality and whenever he entered a room, he left an indelible impression. First of all, he was enormous. He skied over his comrades and heaved rocks further than anybody. It was rumored that he took out his first police officer with a rock when he was barely twelve years old at a huelga (strike). When the neighborhood mobilized, the combat-tested youth darted into the streets with bandanas covering their faces and towels soaked in water to withstand the tear gas. But not Franklin. There was no hiding a dirigente (leader) who stood 6 6’, 245 lbs. Everyone knew his stance. When news crews interviewed the balaclava-clad youth, Franklin came out on national television; showing his face, confidently looking into the cameras and denouncing the politicians and their cronies, unhesitatingly, without fear of the reprisals that would follow. With complete self-assurance, he stated “If the chivatos (snitches) and police want to come for me, let them come for me. I won’t live in fear in my own country.” Due to his presence and the way he took up space, his running mates baptized him la yegua, the mare or big horse.

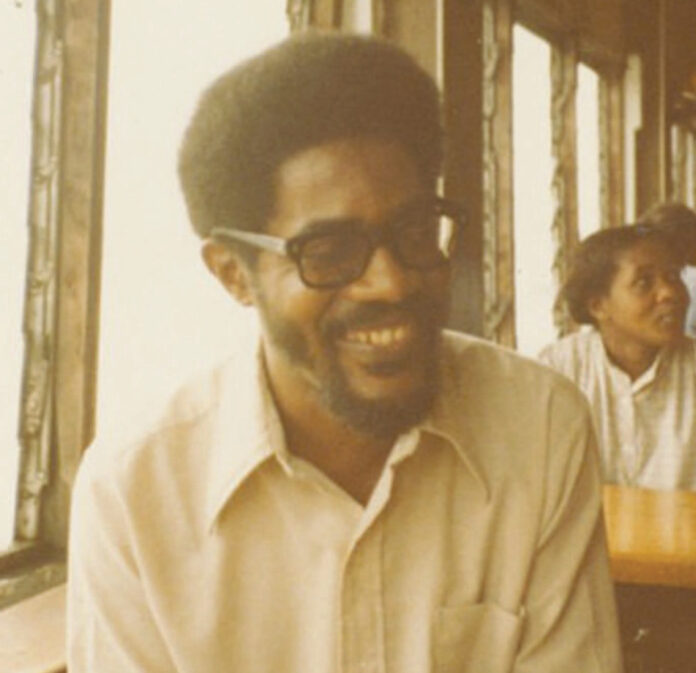

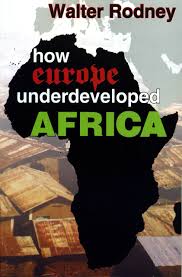

La yegua was also a social butterfly. He could talk to the most dispirited grandmother, the loneliest house wife or a classroom full of agitated high school students. He never met an audience he disliked. When he took stage, the room stopped. Audiences were glued to his every word. His mentors bragged that “he threw pages to the left,” meaning that he read voraciously to better understand Latin America’s history of struggle, and the Dominican Republic’s place in this continent wide insurrection. It was these skills that propelled him into a leadership position within el MPD. The top cadre reasoned that once they won over Franklin, they had won over half of Villa Altagracia’s 175,000 inhabitants.

Spellbound

Yahaira was from Villa Altagracia as well but she had left with her family to live in Providence, Rhode Island when she was three years old. Her father was a highly-respected judge who felt iron hot contempt for Franklin and the tigueres (riff-raff) who insisted upon interrupting business with protests that shut down the highways and commerce of the entire town.

Though Yahaira still dreamt in Spanish, truthfully she had a greater command of a foreign tongue. She had graduated at the top of her class as a duel English and Black Studies major at Princeton University. Every summer she returned home to visit her family. She understood little about the national liberation war—the crucible of fire that gave birth to Franklin and his rage. Late night police raids, going underground for months in a neighboring town and wearing police bullets as badges of honor were as foreign to her as bell hooks, James Baldwin, Jesmyn Ward and Richard Wright were to Franklin.

Two destinies, drifting in different life orbits, collided in the summer of 2003. Yahaira was out partying with her cousins when she met Franklin who worked as a bouncer at Villa Altagracia’s largest club, El Caribe. The first time their eyes interlocked, they both felt their knees wobble.

Yahaira was petite, with what the locals called, a guitar shaped body. Franklin—in addition to being a colossus—had a face cut of white granite, with sharp angular cheekbones. He was a heartthrob, and knowing as much he used this trait to call upon his female contacts to help the movement out with favors, lending money to the movement or hiding contacts, who were on the run from the state.

The pair attracted a great deal of attention on their own but together they were the talk of the town. Franklin towered over Yahaira and jokingly swept her off her feet and tossed her over his shoulder to tease her. Yahaira searched for a sidewalk or a park bench in order to reach his lips and kiss him. After dating for the summer weeks, they felt such intense passion that they discussed the option of marriage. They decided to tie the knot so that Franklin could eventually be with her in the U.S. The months the newlyweds spent apart from one another marched at a tortoise’s pace. Yahaira returned every other month, anticipating the granting of her husband’s visa. She became pregnant and now the couple prepared for parenthood with 1,600 miles of distance between them.

After a sixteen month wait, the couple was called to the U.S. embassy. When the consulate agent returned Franklin’s passport with a visa, they looked at each other, wondering if they should cry out of celebration or out of fear. They were about to embark upon a reality that had snuck up on them both, the reality of marriage, twenty four hours a day, seven days a week.

Disillusioned

The marriage was doomed to fail before the pair shared their one thousandth kiss. Franklin had his culture. Yahaira had hers. They both believed in reading, studying and hard work but for completely different purposes. One was the American dream. The other was the American nightmare. Franklin was never meant to leave the only surroundings he ever knew. New England would pose a threat to his identity and his ego, more formidable than a politician’s bribe or a policeman’s bullet.

Yahaira lived in Providence with her parents and their newborn baby boy, Johan. Franklin weighed his options. Follow the “American illusion” or remain where he was indispensable. Overnight, Villa Altagracia’s highly-decorated marksman became Providence’s stay at home dad. In February 2011, when he exited JFK airport without a coat into the Northeast’s 23 degree, he instantly knew he had made a grave mistake. It took less than one week for him to grow depressed with his new reality. He who stood almost 7 feet tall felt dwarfed by his new environs.

Franklin began to drink and put on weight. Something about American food made him feel lifeless and bloated. Like too many immigrants, he put on the freshman 20. He wasn’t sharp like he had been and his face grew scruffy. La yegua forgot the days before when he rolled out of bed with a glock in one pocket and a book in the other. Villa Altagracia’s Field Marshal contemplated turning his back on the dream and the dreamers but his pride weighed heavy on the see-saw of identity. How would it look if he returned home—from the country of miracles—empty-handed, plump, soft, wifeless and defeated?

Dispirited

He who had commanded a people’s battalion before the onslaught of military police now changed diapers and heated bottles for a living. Without a dollar to his name, he depended on Yahaira for everything. If he wanted mofongo, he had to tell his wife in advance. When they argued about the littlest thing, he raised his voice blaming her for pressuring him into leaving his natural habitat. But his voice dissipated before her screaming retorts. He tried to work but he didn’t yet have a good command of the English language. Yahaira resented his “ignorance” and wanted her own free time to hang out with the cultivated and educated spoken word and hip hop crowd that she was accustomed to. The blame game made them both bitter and at twenty three they carried a mutual resentment, usually reserved for a couple twice their age.

Yahaira kicked him out. The man who had 50,000 homes in his old town, had nowhere to go. He roamed the desolate, frost-bitten streets of Providence trying to remember who he was. The first night he slept inside of a Peter Pan bus station. He began to work odd jobs overnight at clubs cleaning up after the last drunken clientele left at three a.m. He slept on buses during the day. Because of his mare-like size, he was soon asked to work security at the clubs, which was a big upgrade from being an errand boy.

Fortunately for him, Franklin grew up in Villa Altagracia with two second cousins who had immigrated to Providence five years before him. Lost in dead-end, minimum wage jobs that required them to work the graveyard shift at an industrial laundry, his contemporaries found themselves knee deep in the world of hustling. They sold drugs on La Broa—the main drag in Providence’s Dominican community—and in the poor, white suburbs of Cranston, Barrington and Narragansett. They told him if he did a 10pm to 8am shift with them a few times a week, he could earn $125 cash per night. This new rhythm, combined with $75 all-night shifts as a bouncer, earned him a steady income. He learned to hide crack cocaine under trash cans and waited for junkies to come around who needed it. He led them to it, careful not to pick it up and implicate himself in the distribution process. Even the smallest quantity of crack was a guaranteed 10 years federal times under the Rockefeller Drug Laws. Other times he brought cocaine directly to white customers who lived in safer condominiums in the outskirts of Providence. When he made a drop off, he waited around for at least twenty minutes, confident his clientele would need a resupply. A few random customers turning into a dozen plus dependents who called him at all times of the day and night. Cocaine was a safer hustle and earned less jail time than its bastard offspring, crack. Soon he needed to trade in his old hoooptie for a Toyota Highlander to keep up with the runs. It was an ugly world—far removed from the ideals he came from—but he felt defeated when he considered the options. Pride is a heavy stone that weighs on the seesaw of life.

Seduced

When you are poor, money is seductive. When your pockets are full, you feel no pain. Or so the poor think. Franklin was no different. He did anything to stack up more money. Just as the sun drifts far away from the Northeast in December, leaving New England in a four month frozen stupor, Franklin gravitated away from his former world of conviction and righteous action.

The streets were disorienting and depoliticizing. Quick money brought quick power. Scorned, he refused to check in with Yahaira, passive-aggressively leaving her to think he was dead. When he yearned for her, he focused on the final image he had of her patronizingly cursing him out and slamming the door in his face. For a man whose reputation back home was based on loyalty, this was unforgivable. He would freeze to death before he would crawl back to implore her to let him stay with her and their son Johan, who he affectionately called Bombi. He missed his newborn but knew he and Bombi would always be close as he came of age. Lost, estranged and muddle-headed, Franklin was at least his own man again. He promised himself, he would never again be anybody’s burden.

Unstoppable

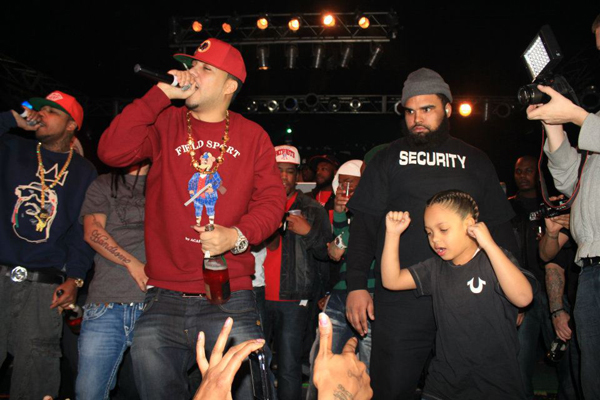

Franklin began to lift weights again. He returned to the old form that had earned him his nickname. The higher end Latino dance clubs hired him as their doorman. No one, regardless of who knew who, could get into the club without settling accounts with him. Sneakers, Timberlands, baggy jeans, hoodies, and “a sausage fest” were all justifications for a de facto fine, imposed by Providence’s smooth-talking, Dominican doorman. When he rejected individuals or groups at the door, he always opened up a path for their rehabilitation. “No Tims tonight my brother unless you choose to do the right thing.” Or “Sorry hermanita (young sister), those sneakers are a no go. But if you bless us exploited toilers, there could be hope for you.” There was a short Italian bouncer Tony who was a sanitation worker during the week. In his black trenchcoat and polished shoes, he was as slick as Franklin. The two made a formidable team.

If they suspected the revelers carried marijuana, ecstasy or mollies, he patted them down and seized their drugs. They pretended to throw them away in disgust, only to hold on to them and resell the narcotics back to the post 3am crowd at inflated rates. Now la yegua flipped thousands of dollars in a weekend. He arrived at daybreak to his cousin’s’ apartment, squinting as the blinding sun rose above him, smuggling its rays through the curtain blinds.

Exhausted but accomplished, he threw down hundreds of crumpled bills onto his mattress. He didn’t even count the money as he neatly folded it into stacks, but he knew that thousands of dollars were flowering into tens and hundreds of thousands of dollars. He despised money but grew addicted to the freedom it signified. Having never opened a bank account nor written a check, he opted for a makeshift safe in his trunk. Underneath his work out gear, protein shakes and supply of daily fruit, he hid stacks of money in a small chest with a combination lock where most car-owners had a spare tire. The rest of the stacks he sent off to the MPD in the capital. But they suspected something was off. No amount of money could replace the loss of their former Minister of Defense. But Franklin was on top, he was high off of life.

Estranged

He had not seen his son, Bombi in six months. More hard-headed than ever, he vowed to see Bombi but without exchanging a single word with Yahaira.

Both mother and son were elated to see the gentle giant. He held his prodigy for ten minutes and silently listened to her half-apologetic, self-righteous diatribe before condescendingly tossing a tightly taped, thrice folded trash bag at her. Before she could count the four thousand plus dollars in cash distributed in four envelopes, Franklin had descended back to the street. She called after him, but all he heard were the texts streaming in from three other girls and her last cold words at the door months before. Yahaira wanted to take him to court but Franklin had never followed up with his residency papers. To the immigration bureaucracy and city hall, he was a ghost, a non-person. That’s the way he liked it. The U.S. of A. didn’t like him and he didn’t like the U.S. of A. Before heartlessness, the sensitive turn heartless. He saw no future here for himself. His future was back with his people and Bombi would one day understand this.

Coveted

In the Divided Snakes of America, money is freedom. He who has it is the freest of free men; he who doesn’t is a prisoner to scarcity. Franklin was propelled to local stardom. Fast cash meant nicer clothes, a new SUV, street credibility and an abundance of women to blow his money on. Part of his humility faded into the memories of his youth, the others into the mountains of cash that laid before him.

Franklin was inside of one woman, thinking about three others. Before returning to one girlfriend, he saved numerous text messages to drafts in his phone so that he could later send them quick and not provoke her jealousy. He carried two phones, one for profits and one for expenses. No girl he dated knew this so he could never be caught red handed. He couldn’t be in the here and now because he was always everywhere, anticipating the next adventure. Hustling was his addiction and dating multiple women was merely an extension of the constant adventure.

He, who was once somebody, then nobody, emerged as somebody again.

He took all of his people skills, and without an insurrectionary outlet, invested them in the world of hustling. He had two cars. An old beat up 1995 Geo Tracker jeep, for drop-offs and collections, and a $50,000 silver 2004 Escalade, to show off on the town. Every time the police stopped him in his larger-than-life Cadillac, he wore a smirk on his face, as they unsuccessfully searched for illegal narcotics, which he left in his old jalopy. He was the David Ortiz or Big Papi of the underground. Although he felt a deep-seated anger towards the ghetto surveillance, he was as polite as a UN diplomat, addressing them with his thick accent, but maintaining a formal demeanor, just to rub it in their faces that he was one step ahead of them.

One Saturday night, a young drunk driver rear-ended his car. Both the kid and Franklin’s crew grew nervous that the police were not far behind to look into the matter. Panic stricken, Franklin gave the petrified, inebriated teenager $800 and told him to get lost. The kid held the money and tried to compute how his careless texting while driving turned into his salary from three weeks of work at Subway. Seeing him pensive, Franklin gave him a cocotazo (a slap on the head) and told him to get the fuck out of there. Franklin’s destiny was precarious and tragedy was only one 911 call away.

Loyal

Franklin rented a permanent hotel room in Washington Heights, Providence and Brockton. Other drug dealers paid him to crash there so he, again, came out winning. When another hustler charged up a large bill in pornography, Franklin pinned his neck to the wall. Even within his gluttony, la yegua was reasonable.

Out of touch with his MPD family, la yegua stopped reading and projecting their unique worldview. Still, he was not your average hustler. He applied his acumen for insurrection to street adventurism. With all of the women he chased, he picked up Portuguese and Cape Verdean Kreolu. He achieved a certain street fluency and was soon a polyglot. Franklin, who only six months before was a sloth, still in pajamas and in a bathrobe at one in the afternoon, couching it up with a three-year-old, was now on the move. And nothing could stop him.

Still, he was careful not to squander money. He was generous but intelligent. But when it came to women, he knew how to throw down. On a double date his pana (partner) scrutinized the check in front of two Brazilian girls from Marlboro. Franklin rapidly but calmly grabbed the bill out of his hand, without the girls noticing. He switched the conversation, hiding the check under the table. Without confirming the exact price, he removed four $100 bills from his pocket and placed them with the check in the waitress’s folder. Later that night he told his pana full, “Never review a check in front of women. Cover it and figure it out later but never flinch in front of a woman.” Machismo and the code of the streets were not always synonymous with humility.

Invincible

La yegua cornered markets in Providence, Boston, the Bronx and everywhere in between. He checked in with his compañeros back home in Villa Altagracia but felt worlds removed from their everyday struggles. They missed him and urged him to come back home.

This was the era when Dominican baseball players were beginning to dominate Major League Baseball. Manny Ramirez, David Ortiz and Pedro Martinez were rewriting baseball as America knew it. Franklin wore a Red Sox hat everywhere he went. Some Yankee fans challenged his right to represent the Red Sox south of Bridgeport, Connecticut. These incidents were never uptown or in the Bronx, where everyone knew him and the masses of Dominicans rooted for the Red Sox. Twice in Manhattan, Yankee fans south of 96th St. made fun of his jersey and spit on him during the 2005 Red Sox-Yankee playoff series. He calmly left them both in a pool of blood and exited the scene before they could make heads or tails of the situation. A bouncer came out and demanded his ID. He looked back smiling, rattling out his signature shit-talking lines: “Are you serious verdugo (slang for dude, but means executioner?) What are you going to do? Put me in detention? We waited 85 years for this!” It was not his style to look for problems but he resolved them when he had to.

Yahaira reached out to her old confidante, his parents and anyone else to patch things ups. Villa Altagracia’s most humble was seeing so much money he told her, her uppity judge father and her Princeton education, to go fuck themselves. A man scorned on the upswing was impossible to pin down. Impatient, she would have to wait to catch him when his fall from grace arrived, as it inevitably does for every hustler. Resentment has a way of blinding a man’s heart. Still, he visited his son once every few weeks but the visits were brief. When there were dollar signs to be stacked, little else mattered. Now Yahaira was the one who talked to a voicemail.

Alienated

Franklin hated who he had become but he no longer knew who he was. Accustomed to the underground, he did not mind illegality. He wasn’t a slave to anyone’s caprices, not Yahaira’s, her well-off parents nor those of Rhode Island’s courts. Part of him secretly hoped he’d be caught soon enough so he could go back to being the man who had nothing but had everything. Now he had everything but had nothing.

La yegua still had his political training but the ego is a terrible thing. It spiraled out of control. He endeared himself with women using his muela (game) and soft smile to charm them. He never slept in the same place. That was a decision he left to the night. If a woman was well-off and acted drunk and sloppy, he pocketed what he could from her purse or apartment. The street reasoning was that if anyone “got caught slipping,” they themselves were to blame. Besides, he concluded, the money he expropriated funded the movement back home. His moral code grew out of the stark social contrasts that characterized his Dominican homeland. He was lost but loyal. A hustler but a hustler hammered out of a revolutionary street ethic who refused to take advantage of his own people.

The chase became an addiction. But no one can live on a permanent high. What goes up must come down. With the women he enamored, he mentioned using a condom but in the heat of the passion it was a hindrance and he rarely used one. A “real man” and a “limp dick” have no time for each other. He had more than one scare with pregnancies and STD’s. The ebbs and flows began to play with his mind. He wondered how many “hustlers” would today be a Bunchie Carter or Fred Hampton if there was a community to invest in them, applying their “conversation,” street smarts and talents to the future.

Reunited

The Secretariat, the highest body of the MPD, flew an elder leader, Felix, a veteran of the 1965 uprising, to Providence to reel Franklin back in. Felix trained Franklin, his godson, in Marxist ideology and street tactics ten years before. The leadership was deeply saddened, first by Franklin’s abrupt self-exile and then, by his fall from revolutionary grace.

They sat down to dinner. Felix threw his hands up in disbelief:

“Who have you become m’ijo? This is what we taught you? You are that weak that for some rum, yankee dollar signs and women, you are going to sell us out?”

La yegua was both angry and ashamed. On the defensive, he fired back: “Fuck the movement! This is a different world. What is the movement doing for me? This woman fucked me over!”

He knew he was wrong to betray three generations of self-sacrificing MPD warriors, but a broken heart and bruised ego conspired against his MPD training. A satellite out of orbit, his feet could not find any familiar ground to touch.

Felix and his godson never even started their meal. Franklin jumped up pushing his seat back, asserting “I don’t know who I am anymore.” He sent the sixty three year old warrior off with a hurried apology, a trash bag full of Jordan sneakers, new designer clothes and a tightly wrapped plastic bag. Disgusted, Felix threw the bag into his suitcase in the trunk of his brother-in-law’s car. Three weeks later he delivered the trash bag to three MPD leaders in Villa Altagracia’s humble El Caobal neighborhood. The tightly wrapped double trash bag had $7,000 in it, and a note that read “We all have a role to play. Keep playing yours and I will play mine.”

Resurrected

Just as fast as his star had rose in the north, Franklin again fell from glory. His own second cousin, jealous of his ascendance, which left them no room to operate, tipped off the police that the trunk of his Geo Tracker was lined with cocaine. Franklin again returned to nobodydom.

The state sent the popular agitator to languish in a cell, where he nostalgically remembered what it felt like to be somebody. A federal judge from Arizona determined that he would be deported, but not before he served twelve years in a federal prison. After two months in the same federal penitentiary where Leonard Peltier was held, in Leavenworth, Kansas, he received a package from Santo Domingo. He unwrapped the package and took out three books, Eduardo Galeano’s The Open Veins of Latin America, The Communist Manifesto, and Pedro Mir’s Hay un Pais en el Mundo. He took a deep breath, kissed a picture of his son, Bombi and opened The Communist Manifesto. There was an inscription from Felix: “We all have a role to play m”ijo.” He began to read, realizing he was just beginning to live.

[1] Skyed is slang for stood taller than everyone else.

[2] The Saints of Santo Domingo tells the untold stories of the dirigentes, elected revolutionary neighborhood leaders who prosecuted the poor’s war for definitive liberation.

[3] Movimiento Popular Dominicano is the oldest Marxist-Leninist party in the D.R. Thousands of its leaders have been targeted for assassination by the Dominican state because of the fear, dating back to 1963, that D.R. could become “another Cuba.”

[4] Spanglish slang for a close partner.

[5] Two slain leaders of the Black Panther Party disappeared as a part of the FBI’s covert COINTELPRO program.

[6] Made a mistake and acted careless

[7] Dominican national poet.